Epilepsy in childhood

Epilepsy is a neurological condition (affecting the brain and nervous system) where a person has a tendency to have seizures that start in the brain.

The brain is made up of millions of nerve cells that use electrical signals to control the body’s functions, senses and thoughts. If the signals are disrupted, the person may have an epileptic seizure.

Not all seizures are epileptic. Other conditions that can look like epilepsy include fainting (syncope) due to a drop in blood pressure, and febrile convulsions due to a sudden rise in body temperature when a young child is ill. These are not epileptic seizures because they are not caused by disrupted brain activity. See more about what is epilepsy?

What happens during a seizure?

There are many different types of epileptic seizure. The type of epileptic seizure a child has depends on which area of their brain is affected.

There are two main types of seizure: focal seizures (previously called partial seizures) and generalised seizures. Focal seizures affect only one side of the brain and generalised seizures affect both sides of the brain. Generally, adults and children have the same types of seizure. However, some may be more common in childhood than adulthood (for example, absence seizures which can be very brief and are often mistaken for ‘daydreaming’ or not paying attention).

- jerking of the body

- repetitive movements

- unusual sensations such as a strange taste in the mouth or a strange smell, or a rising feeling in the stomach.

In some types of seizure, a child may be aware of what is happening. In other types, a child will be unconscious and have no memory of the seizure afterwards.

Some children may have seizures when they are sleeping (sometimes called ‘asleep’ or ‘nocturnal’ seizures). Seizures during sleep can affect sleep patterns and may leave a child feeling tired and confused the next day.

Why does my child have epilepsy?

Some children develop epilepsy as a result of their brain being injured in some way. This could be due to a severe head injury, difficulties at birth, or an infection which affects the brain such as meningitis. Epilepsy with a known structural cause like this is sometimes called symptomatic epilepsy.

Some researchers now believe that the chance of developing epilepsy is probably always genetic to some extent, in that anyone who starts having seizures has always had some level of genetic tendency to do so. This level can range from high to low and anywhere in between.

Even if seizures start after a brain injury or other structural change, this may be due to both the structural change and the person’s genetic tendency to have seizures combined. This makes sense if we consider that many people might have a similar brain injury but not all of them develop epilepsy afterwards.

How is epilepsy diagnosed?

A diagnosis of epilepsy may be considered if your child has had more than one seizure. The GP will usually refer them to a paediatrician (a doctor who specialises in treating children). You (and your child if they can) may be asked to describe in detail what happened before, during and after the seizure.

Having a video recording of the seizure can help the paediatrician understand what is happening.

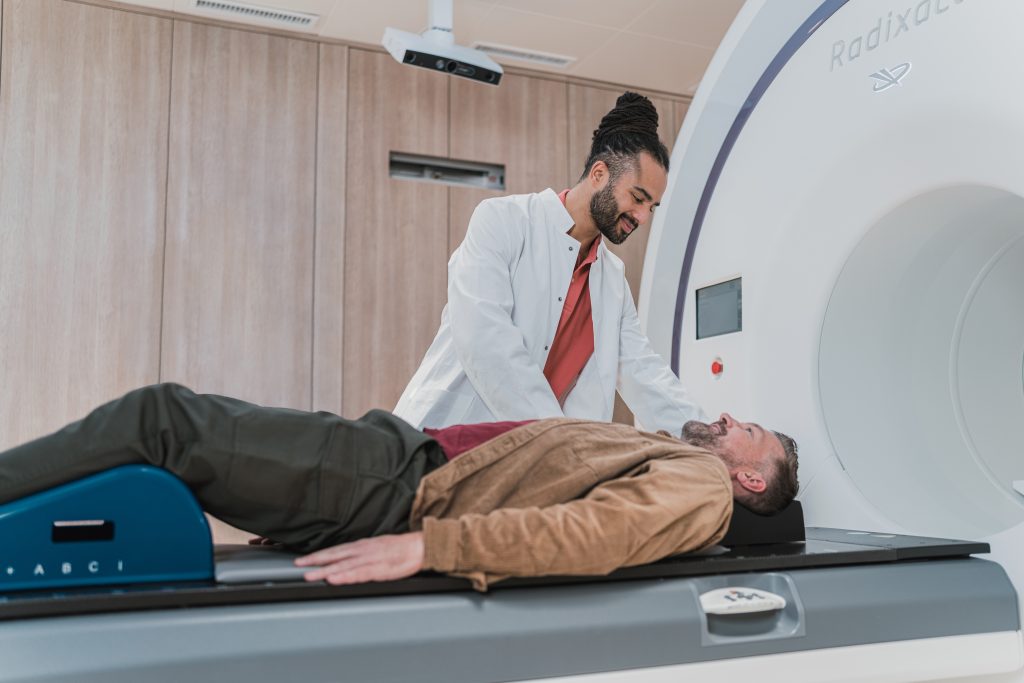

The pediatrician may also suggest a few tests to help with the diagnosis. The tests alone cannot confirm or rule out epilepsy, but they can give extra information to help find out why your child is having seizures.

What is a childhood epilepsy syndrome?

If your child is diagnosed with a childhood epilepsy syndrome, this means their epilepsy has specific characteristics. These can include the type of seizure or seizures they have, the age when the seizures started and the specific results of an electroencephalogram (EEG).

An EEG test is painless, and it records the electrical activity of the brain.

Syndromes follow a particular pattern, which means that the paediatrician may be able to predict how your child’s condition will progress. Syndromes can vary greatly. Some are called ‘benign’ which means they usually have a good outcome and usually go away once the child reaches a certain age. Other syndromes are severe and difficult to treat. Some may include other disabilities and may affect a child’s development.

Treatment for children

Your child’s GP is normally responsible for their general medical care. The GP may refer your child to a paediatrician or paediatric neurologist (a children’s doctor who specialises in the brain and nervous system). An epilepsy specialist nurse may also be involved in their care.

Young people usually start to see a specialist in adult services (a neurologist) from around 16 years old.

Anti-epileptic drugs

Most people with epilepsy take anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) to control their seizures. The paediatrician can discuss with you whether AEDs are the best option for your child. Although AEDs aim to stop seizures from happening, they do not stop seizures while they are happening, and they do not cure epilepsy.

Most children stop having seizures once they are on an AED that suits them. Like all drugs, AEDs can cause side effects for some children. Some side effects go away as the body gets used to the medication, or if the dose is adjusted. If you are concerned about your child taking AEDs you can talk to their paediatrician, epilepsy nurse, GP or pharmacist. Changing or stopping your child’s medication without first talking to the doctor can cause seizures to start again or make seizures worse.

Although AEDs work well for many children, this doesn’t happen for every child. If AEDs don’t help your child, their doctor may consider other ways to treat their epilepsy.

Ketogenic diet

For some children who still have seizures even though they have tried AEDs, the ketogenic diet may help to reduce the number or severity of their seizures. The diet is a medical treatment, often started alongside AEDs and is supervised by trained medical specialists and dietitians.

Epilepsy surgery

It may be possible for some children to have epilepsy surgery depending on the type of epilepsy they have and where in the brain their seizures start. Epilepsy surgery involves removing a part of the brain to stop or reduce the number of seizures a child has.

Will epilepsy affect my child's life?

You may not be able to predict how epilepsy will affect your child’s life. However helping your child to manage their seizures and be open about their feelings can make a positive difference. Help your child’s school understand their condition to ensure they get the most out of their school and education.

Triggers for seizures

Some children’s seizures happen in response to triggers such as stress, excitement, boredom, missed medication, or lack of sleep. Keeping a diary of their seizures can help to see if there are any patterns to when seizures happen. If you recognize triggers, avoiding them as far as possible may help to reduce the number of seizures your child has.

Getting enough sleep, and well-balanced meals, will help keep your child healthy and may help to reduce their seizures.

Immunization (vaccination)

Some parents are nervous about immunisation, whether or not their child has epilepsy. The Department of Health recommends that every child is immunised against infectious diseases. This includes children who have epilepsy. If you are concerned about immunisations, your child’s GP or paediatrician can give you more information.

Behavior

For some children, having epilepsy and taking AEDs will not affect their behaviour. However, some people may notice a change in their child’s mood or behaviour such as becoming irritable or withdrawn. Some children may be responding to how they feel about having epilepsy and how it affects them. They may also want to be treated the same as their siblings or friends and to feel that epilepsy isn’t holding them back. Encouraging your child to talk about their epilepsy may help them feel better.

Behaviour changes and problems can happen for all children regardless of having epilepsy and for many, may just be part of growing up. In a few children, irritable or hyperactive behaviour may be a side effect of AEDs. If you have concerns about changes in your child’s behaviour, you may want to talk to their doctor or epilepsy specialist nurse.

Leisure activities

Most children with epilepsy can take part in the same activities as other children. Simple measures can help make activities such as swimming and cycling safer. For example, making sure there is someone with your child who knows how to help if a seizure happens.

Can epilepsy change as children get older?

Seizures may change over time, either in type or frequency. Some children outgrow their epilepsy by their mid to late teens. This is called ‘spontaneous remission’. If they are taking AEDs and have been seizure-free for over two years, their doctor may suggest slowly stopping medication.

How might my child feel?

Having epilepsy can affect a child in different ways. Depending on their age and the type of seizures your child has, the impact may vary.

For some children having a diagnosis of epilepsy will not affect their day-to-day lives. For others it may be frightening or difficult to understand. They may feel embarrassed, isolated or different in front of their peers. Encouraging your child to talk about their concerns may help them to feel more positive.

Most children with epilepsy will have the same hopes and dreams as other children and seizures may not necessarily prevent them from reaching their goals.